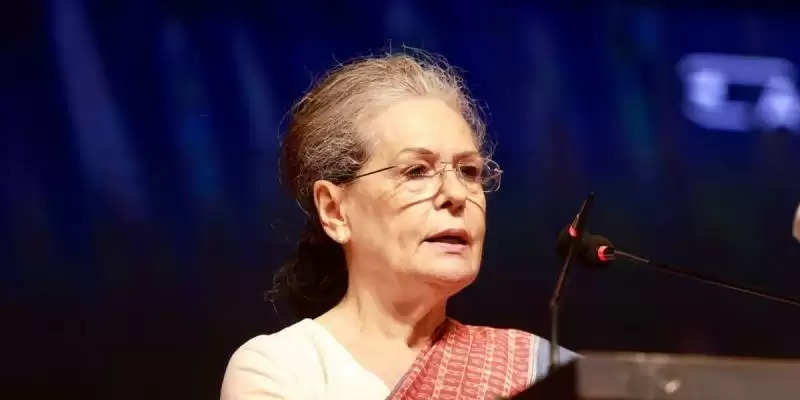

Sonia Gandhi Never Mentioned Karnataka's "Sovereignty," Yet SC View Disproves Modi's Allegation of "Secessionism"

New Delhi: On May 6, the Congress party's official Twitter account posted a message attributed to Sonia Gandhi, the chair of the Congress parliamentary party, saying: "The Congress will not allow anyone to pose a danger to Karnataka's reputation, sovereignty, or integrity."

It is likely that someone on the Congress's social media team completely mistranslated the speech because it did not contain this sentence or any words even vaguely similar to these when she delivered it in Hubbali that day while supporting her party's candidates in the upcoming assembly election, nor has the BJP circulated a clip with those words.

Whatever the case, Prime Minister Narendra Modi seized on the Congress's tweet and asserted on May 7 that Karnataka lacks sovereignty and that anyone who claims it does is pushing for secession. A typical newspaper headline on PM Modi's retort read, "Congress Shahi Parivar agitating for Karnataka secession: PM Modi."

The BJP complained about the allegedly offensive statement to the Election Commission on Monday, May 8. In response to the complaint, the poll panel wrote to Mallikarjun Kharge, the president of the Congress, asking him to "provide clarification and take rectification measures in respect of the social media post that has been put up on the Official INC Twitter handle and attributed to Chairperson CPP."

Regardless of whether Sonia Gandhi actually said what she is accused of saying or whether the prime minister correctly interpreted the impugned words, the Supreme Court's interpretation of the Indian Constitution is unmistakable: the Indian people have legal sovereignty, while the Union and state governments share political sovereignty.

Most importantly, one cannot advocate independence by referring to Indian Union states as "sovereign." In his dissent in a seminal 1962 decision, K. Subba Rao, one of the former Chief Justices of India (CJI), very specifically referred to states as "sovereign" in their designated realms. Had he not done so, he would have been guilty of the offence of inciting secession.

On December 21, 1962, the Supreme Court of India issued its ruling in State of West Bengal v. Union of India, which provides some insight into this issue.

Land purchase was the topic of this ruling, which was given by a six-judge panel. The Union of India intended to purchase a number of coal-bearing lands in West Bengal under the Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act, 1957, which was passed by parliament. The state launched a lawsuit, claiming that the Act did not apply to lands that belonged to or were held by the state and that, even if it did, the Act was outside the purview of parliament's legislative authority.

On behalf of the majority judges, Justices Jafer Imam, J.C. Shah, N. Rajagopala Ayyangar, and J.R. Mudholkar, the then Chief Justice of India, B.P. Sinha, held that it was obvious from a proper interpretation of the relevant provisions of the Act that it also applied to coal-bearing areas that belonged to or were owned by the state government.

The majority of the judges decided that the preamble of the Act did not support the claim that it was exclusively designed to acquire individual rights in coal-bearing areas, not state rights.

Judge Subba Rao stated in his dissent that the Act is "extra vires" insofar as it gives the Union the authority to acquire state-owned assets, including coal mines and coal-bearing fields. He claimed that the Indian Constitution divides political sovereignty among the constitutional institutions.that is, the Union and the States, who are legal persons with property and who carry out their functions using the means established by the Constitution. He asserted that the Indian constitution supports the federal model and divides sovereign powers between the Union and the States, the co-ordinate constitutional bodies. This idea suggests that one cannot tamper with another's government's operations or tools unless the constitution expressly permits it.

According to Justice Subba Rao, one of the implicit rights of the sovereign includes the ability to seize a citizen's property for a public good. He asserted that the Union and the States share this sovereign power. A sovereign's ability to acquire property is implicitly limited to that of the governed because a sovereign is powerless to do so. He came to the conclusion that the Union could only legally acquire state property with mutual consent.

The majority justices, while undoubtedly disagreeing with Justice Subba Rao on the Act's validity, did not expressly disagree with him on the issue of interpreting sovereignty.

According to the majority of the judges, it is incorrect to say that the States have complete sovereignty. It's important to remember that Judge Subba Rao did not make that suggestion either.

According to the majority of judges, a parliament that has the power to overthrow a State cannot be said to lack the authority to legislate the acquisition of the State-owned property under the principle of absolute state sovereignty.

The ability of the Union to legislate in regard to the property located in the States would remain limitless, they argued, even if the constitution were to be interpreted as a Federation and the States were to be considered sovereign qua the Union. It demonstrates that the majority of judges also thought it was acceptable to say that the Union and the States can both be regarded as sovereign entities.

One of the five concerns in this case was the question that the constitution bench had framed. It questioned: Does the State of West Bengal, as claimed in paragraph 8 of the plaint, possess sovereign authority?

In legislative and executive concerns, there is without a doubt a division of authority between the Union and the States, but this does not always indicate political sovereignty. The people of India, who, according to the preamble, have sincerely resolved to organise India into a Sovereign Democratic Republic for the purposes outlined therein, hold the legal sovereignty of the Indian country.

"The Union of India and the States share political sovereignty, with the Union bearing a heavier weight than the States. The Government of India and the States are given the status of quasi-corporations under Article 300, giving them the right to sue and the potential to be sued in relation to their respective affairs. According to the Constitution, the Governor is given executive power over the State under Article 154, and he may exercise it either personally or through offices that report to him.

The vast authority granted to the Parliament by the Constitution to change the boundaries of States and even to annihilate them appears to work against the premise of the sovereignty of the State. There is no safeguard in the Constitution against changing the borders of the States.

According to Article 2 of the Constitution, the Parliament may admit new States into the Union or establish them under such terms and conditions as it deems appropriate, and Article 3 of the Constitution grants the Parliament legal authority to create new States through the redistribution of existing States' territories, the joining of two or more States or portions of States, the joining of any territory to a portion of a State, the enlargement or contraction of existing States' areas, the alteration of existing States' borders, and other means.

As a result, Parliament is given the legal ability to change any State's boundaries and reduce its territory, even to the point of destroying a State with all of its authority. Given the scope of Parliament's authority, it would be difficult to argue that the same Parliament that is capable of overthrowing a State is also incapable of effectively acquiring by laws created for that purpose the property owned by the State for governmental purposes.

It was argued that if the State's property could be acquired by the Union, as the learned advocate-general of Bengal eloquently put it, "the Union could acquire and take possession of Writer's buildings where the Secretariat of the State Government is functioning and thus stop all State Governmental activity."

The majority judges argued that there was no question that the Union would be abusing its power of acquisition if it took such action, rather than using it. However, in law, the possibility of abuse of a power has never been a ground for denying its existence; rather, its existence must be assessed in light of entirely different factors.

These judges added that they were unable to understand the claim that if the Constitution were to be interpreted as a Federation, with the States serving as the federative units, such a status would inevitably entail a restriction on or denial of the Union's ability to acquire State property in order to carry out its legislative powers. It was said:

As a result, even though the States are considered as the Union's sovereigns, the Union nevertheless has unfettered ability to legislate about property located in the States, and State property is not exempt from its application.

The Supreme Court stated in Swaraj Abhiyan v. Union of India (2017) at paragraph 51 that the concept of federalism as it exists in India cannot be explained in one or two sentences; rather, a thorough examination of each and every provision of the constitution would inevitably show that India has divided sovereignty into the Center and the States on the one hand and the Union on the other. In its own way, each powerhouse is independent.

Justice K. Ramaswami made the following observations in S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994) at paragraphs 247 and 248 of his separate judgement:

"The State as defined by the Constitution is federal in nature and autonomous in the exercise of its legislative and executive authority. The State, however, has no authority to declare independence or secession because it is a creature of the Constitution. State is qua the Union is qua federal. Both organisations serve as coordinating institutions and should exercise their respective authority with flexibility, understanding, and accommodation in order to uphold and advance the constitutional objectives, including secularism, and to provide socioeconomic and political justice to the populace.

In this ruling, Judge Ramaswami was merely restating the obvious, as suggesting that the states are sovereign in addition to the Centre does not imply that they have the authority to leave the Indian Union. The phrase has always been used in relation to the States to imply cooperative federalism, which is that they assert their sovereignty alongside the Center rather than in opposition to it.

In J.P. Rao v. Union of India (2014), a PIL, the division bench of Chief Justice K.J. Sengupta and Justice P.V. Sanjay Kumar made some observations.

Even though the States in the Union of India are recognised as constitutionally separate legal entities by Article 1 of the Constitution, the States are said to be enjoying political sovereignty based only on the division of powers between the States and the Union. The people of India, who, as stated in the Preamble, have sincerely resolved to organise India into a sovereign Republic, are in possession of the legal sovereignty of the Indian country.

A democratic form of government acknowledges that sovereignty rests within the people and is exerted either directly or through their chosen representatives, according to the constitution bench's ruling in GNCTD v. Union of India on July 4, 2018.

In Kalpana Mehta v. Union of India (2018), the constitution bench noted that the idea of constitutional sovereignty bound the three wings of the state, all of which were governed by the constitution's framework.

Sonia Gandhi's election speech on May 6, 2023 was given in Hubli, not Ballari, as was incorrectly mentioned in a previous version of this narrative.

.png)